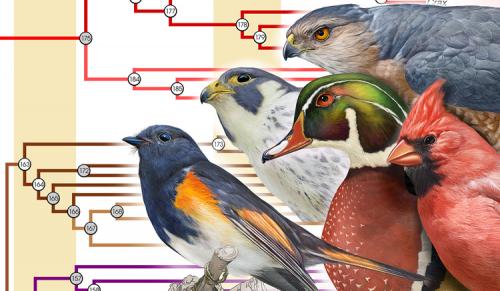

Cardinals and woodpeckers evolved from a hawk-like ancestor and most of the world’s water birds also appear to be a close-knit group, indicating one avian lineage quickly adapted to aquatic environments after most of the dinosaurs died out at the end of the Cretaceous period.

These are among hundreds of other stories that make up the history of birds revealed in a massive Yale-led genomic analysis of 198 species of birds published in the Oct. 7 edition of the journal Nature. The research sheds new light on how all modern birds evolved from the only three dinosaur lineages to survive the great extinction event 66 million years ago.

“This represents the beginning of the end of avian phylogeny,” said Rick Prum, the William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and co-lead author of the Nature paper. “In the next five or 10 years, we will have finished the tree of life for birds.”

In the last decade, the historical origins of ostriches and their relatives the emus have been well established, as it has for ducks, chickens and their relatives. But the evolutionary history of 90% of contemporary birds in a group called Neoaves has remained murky. The early ancestors of thousands of these species appeared to have evolved suddenly within a few million years after the extinction the non-avian dinosaurs.

The research also reveals fascinating relationships among the living birds within the group. For instance, other than the ducks and the cranes, most of the world’s water birds are closely related — suggesting they radiated out across the globe in aquatic niches following the extinction of dinosaurs and did not, as previously thought, evolve from multiple independent lineages. Among other tidbits discovered, the highly visual hummingbirds apparently evolved from nocturnal species of bird, and that “the ancient common ancestor of the cardinal and woodpecker in your garden was a vicious, hawk-like predator,” Prum said.

The completion of the avian tree of life will allow researchers to definitively investigate many outstanding questions in the evolutionary history of birds, Prum said.

“Once we have the complete tree, we can start to study the patterns and processes that have given rise to all the amazing diversity of living birds. That’s when the fun really begins,” he said.

Cornell’s Jacob Berv, formerly of Prum’s lab, is co-lead author of the paper. Researchers from Florida State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences contributed to the study.